Prison Literature

What would have happened, do you suppose, if Malcolm Little, instead of serving six years for petty crimes, had been imprisoned for a much longer time, locked in the conditions of long-term isolation common in what’s euphemistically called “special housing” (as, for instance, the prisoners at Pelican Bay in California are)? He would not have been allowed to receive political books, would not have been able to converse with anyone. The mind that developed through reading and talking in prison during the 1950s would probably have been crushed, and there might have been no Malcolm X.

— Laura Whitehorn

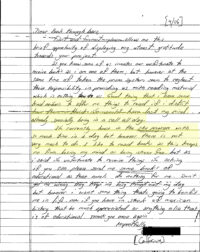

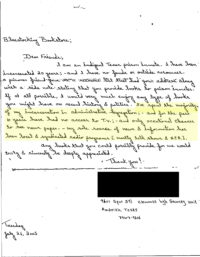

In recent decades, the landscape of U.S. criminal “justice” has changed dramatically (some visualizations at The Society Pages; bibliography at LLRX.com), not that imprisonment hasn’t always been dehumanizing, racist, and generally problematic. For many years, I worked with books-to-prisoners groups, mostly NYC Books Through Bars. These are grassroots, all-volunteer projects that receive letters from individuals in prison requesting reading material of all sorts (sometimes by topic, sometimes by specific title) and then mail them donated books that—ideally—approximate what they’re looking for.

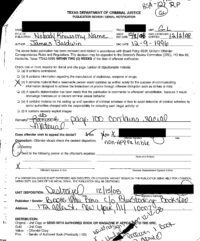

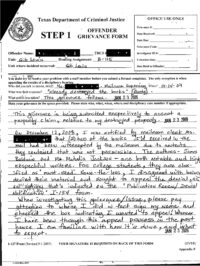

Some years ago, there was an uproar after the federal Bureau of Prisons made a decision (quickly reversed) to get rid of religious books that weren’t on approved lists for prison chapel libraries. Unfortunately, what many don’t realize is that the vast majority of incarcerated people are in state prisons, where they are subjected to the arbitrary policies of the state department of corrections, including with regard to reading materials.

When a book arrives at a Texas prison mailroom, an employee first checks the database to see if the book is already prohibited. If not, said [Texas Department of Criminal Justice staffer Tammy] Shelby, “he’ll flip it over and read the back.” If that provides insufficient information to make a decision, “they scan through it looking for key words” or pictures that would disqualify the publication. “You can pretty much tell by reading the first few pages,” she said. “We rely on them to use their judgment.” (source)

Once we got a form denying a Texas prisoner Invented Lives: Narratives of Black Women 1860-1960 by Mary Helen Washington because “page 29 contains racial material.” Books and magazines have been rejected because they apparently present “a threat to the security, good order, or discipline of the correctional system or the safety of any person” or because information in it might be “designed to achieve the breakdown of prisons through offender disruption such as strikes or riots,” without further explanation. (Some prison mailroom rejections and letters from prisoners are below.)

Why bring up all this now? As you may have heard, one of the largest prisoner resistance movements is underway. Thousands of prisoners in California have been on a hunger strike as part of a fight for human and labor rights (there was a hunger strike in 2011 with the same demands; the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said they would make improvements but have not, hence the renewed action).

Solitary confinement—considered a form of torture, especially long-term—is a common punishment within the prison system. Among the things that can get someone in trouble in a California prison is having particular literature. “‘[E]vidence’ of gang affiliation has included possession of prisoner-rights literature or books like Sun Tzu’s ‘Art of War’ or Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince.’ It has included journal writings on African American history,” Shane Bauer points out. (Incidentally, The Art of War and The Prince, I have observed over the years, are on the unofficial top ten list of requested titles by people in prison around the country.) There is a lot that can be said about philosophies of reading material as proof of (bad) character or predictor of action, or, conversely, as a therapeutic tool, and as librarians we’ve spent more time than most thinking about this. Here I’ll say only that using literature as a criterion of judgment in this way, amid the general violence and toxicity of prison, does nothing to address the wrongness that the prisoners may have done to others, the wrongness that has been done to them, and the systemic wrongnesses that have brought us to this moment of mass incarceration, a “new Jim Crow,” and a correctional officer putting into administrative segregation someone who had a donated copy of Machiavelli in his cell.

Maybe you’ve done library service in a jail or are interested in prison librarianship. Maybe you’ve visited a loved one in prison. Maybe you’ve been locked up yourself. Maybe you grew up with people who got channeled into the detention system in one way or another. Maybe you live in a town where a prison is the largest and most stable employer around. Maybe imprisonment is nothing that you or your community seems to have experienced directly. I think that regardless of which category (or categories) you’re in, we should keep in mind that at least 95% of all state prisoners will be released at some point, and how we approach crime and punishment says a lot about our collective humanity. Former and possibly future prisoners are likely users of your library. Rather than being some separate element of society, they are patrons and would-be patrons.

You can keep up with the hunger strike and support the California prisoners in a number of ways. More generally, there are alternatives to incarceration, organizations for prison abolition and projects of decarceration. And in the meantime, you can always send someone behind bars a good book.

3 comments on “Prison Literature”

Comments are closed.