A Space for Hate: The White Power Movement’s Adaptation into Cyberspace

Introduction

June 10, 2009: James von Brunn logged off his Packard Bell computer, grabbed his keys and strode out the door of his son’s Annapolis apartment. He had moved in with his son and future daughter-in-law two years ago where he paid $400 a month in rent and spent most of his time on the internet. The drive to Washington, DC was only 30 minutes from there, and 88 year-old James cruised along purposefully in his 2002 red Hyundai as he headed west toward the nation’s capital. For a man approaching his 90’s, the one time advertising copywriter, with a degree in journalism, was unusually media-savvy. Before leaving, he checked over the website he had launched for the purpose of selling a self-published book, and sent out a final email to inform his many readers that “they shouldn’t expect to hear from him again.” James also made a few final notations in his notebook that now rested beside him on the passenger seat.

As he drove over the beltway and into the city, everything seemed in order, yet things were not quite right. James thought of the first black American president, Barack Obama, who just days before had made global headlines at a former Nazi concentration camp where he publicly denounced the growing wave of Holocaust deniers. From the president, his mind shifted to the economic recession that had taken away his livelihood, much as it had in 1981, when James took a similar trip to DC to visit then-Federal Reserve Board Chairman, Paul Volker. He felt little had changed since 1981. The real problem was not the recession or progressive politics. The real problem, underscored in his book, had always been the same – it was about the Jews. The newly scribbled pages of the notebook beside him summarized his beliefs. He wrote, “The Holocaust is a lie. Obama was created by Jews. Obama does what his Jew owners tell him to do. Jews captured America’s money. Jews control the mass media.”

James double parked his car on the southbound side of 14th Street next to the National Mall. He glanced long and decisively at the entrance of the museum to his right. The clock on his dashboard read 12:44pm. With that, he opened his driver side door and reached over his notebook to grab a .22 caliber rifle. When he approached the visitor’s entrance of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, the museum’s security guard, Special Police Officer Steven Tyrone Johns kindly opened the door for the old man. James raised his rifle and shot directly into the chest of Johns, the 39 year-old African-American officer who had served as the museum’s guard for six years. From there, James tried to take his firearm, and his rage, into the museum itself, which was filled with visitors and a few Holocaust survivors on the premises that day. The 88-year old man who had just shot officer Johns in the chest was stopped at the doorway by return fire from the other guards. As he had told his ex-wife many times before, James was attempting “to go out with his boots on.” Just after 1:00pm, the lifelong white supremacist and anti-Semite, James von Brunn, lay wounded and motionless on the floor of the Holocaust Museum beside the African-American guard he had just shot dead.

The tragic shooting at the Holocaust Museum in 2009 was not the first time that white power fanaticism has erupted into a deadly shooting spree at the hands of one if its followers. In the last ten years, there has been a violent strain of unhinged racists and white power ideologues that have turned their words of hatred into lethal acts of terror. In 2007 alone, the Federal Bureau of Investigation reported that 7,624 hate crime incidents had been committed across the United States. According to their statistics, almost every year both the volume and severity of these incidents has increased. From Benjamin Williams, charged with setting fire to three synagogues and killing a gay couple in California, to Benjamin Smith, whose own shooting spree through Indiana and Illinois wounded eight targeted minorities and claimed the lives of a Korean doctoral student and African-American basketball coach. Unlike Williams and Smith, the most recent high-profile assailant, James von Brunn, had been on the FBI radar since his failed attempt to take the entire Federal Reserve Board hostage in 1981, claiming they were part of a larger Jewish conspiracy. However, despite their differences in age, background, and notoriety, von Brunn, Williams and Smith each utilized the basic blueprint of the white power movement – racial intolerance escalading into tirade, and hate speech graduating into action. But these three murderers were tied by yet another common thread that both documented and united their paths along a global movement: the internet.

Like von Brunn who utilized his website, Holy Western Empire, to publish his propagandist book, Kill the Best Gentiles!, Smith and Williams also frequented the pages of white power domains such as World Church of the Creator and Stormfront. These are the new Ku Klux Klan meeting halls, the latest Nuremberg rally town squares. Only they do not take place in the backwoods and basements of American subculture, and they are not advertised in the swastikas and shields of the Third Reich. They are websites, globally accessible to everyone via the World Wide Web. Over the last decade, the white power movement has steadily relocated its central base into the decentralized network of cyberspace; from hardcore skinhead gangs to the neo-Nazi party faithful. In this new virtual reality, Klan hoods have been replaced by a much thicker cloth of anonymity, and the book-burning rallies of yesterday have become today’s white power music downloads, chat rooms, and picture galleries of online youth culture. But how did we get here so fast? When did the communication and recruiting strategies of America’s racist underbelly become so proficient, professional, and even popular?

In fact, the concept of mass communicated hate speech is not a recent phenomenon. The paths to organized bigotry, hate crime, and even genocide have often been traced to a few embittered voices in a society brought together in larger numbers by the leading tools of the media of that society. History has revealed this in chillingly proficient ways. From Hitler’s 1930s Nazi ferment that filled the pages of newspapers and bookshelves across Germany calling for all Jews to be cast from society, to the Hutu militia men in 1990s Rwanda, whose radio broadcasts prompted the mass murder of their fellow Tutsi countrymen and women. The relationship between hate speech and mass communication has steadily evolved together hand in hand with every new generation, and the age of the internet is no different.

Since 1995 when the first hate website was launched, until the present day, with over 10,000 sites currently operating across the web, the messages of intolerance and the primary mode for disseminating them have all gravitated onto the internet. But unlike the other forms of communication used to deliver racist and anti-Semitic sentiments to the masses, the internet has brought its own unique properties that not only transmit, but also transform, conceal, and seamlessly merge hate speech into the mainstream of popular culture. Most watchdog agencies firmly agree that the internet, as a medium for white power objectives, has become the ideal “electronic venue that seems particularly suited for recruitment.” This book will examine how the internet, its structure, media properties and online trends, have allowed white supremacists to adapt all the communities of the white power movement into one computer-screen-sized space – shared by 147 million users.

A Space for Hate

A Space for Hate speaks to the media and information topic of hate speech in cyberspace, but more specifically, how its inscribers have adapted their movement into the social networking and information-providing contexts of the modern online community. While many studies in recent years have addressed the notable ways that popular internet culture and cyber trends such as blogging have democratized the community of information seekers and providers, little research to date has addressed the darker element that has emerged from that same democratic sphere. That is, the huge resurgence and successful transformation of hate groups across cyberspace, and in particular, those that promote white supremacist ideas and causes. In 2009, hate speech and white power movement organizations in the United States are on the rise once again, fueled by new issues but with familiar themes. Among them, the election of the first African-American president of the United States, a national economic crisis that has triggered ethnic scapegoating, and an immigration debate centered largely on illegal Hispanic immigrants. These are just some of the emerging social issues by which today’s hate groups have framed familiar messages of blame, anger, fear, resistance, uprising and action.

This book will focus solely on the white power movement by using hate-based websites as a concrete and measurable field for examining racial and ethnically targeted messages in the age of information and technology. Nowhere is this phenomenon more widespread today than within the unguarded walls of cyberspace. The increasingly acceptable domain of anti-Semitic, anti-gay, and racist expression within such commonplace websites as Wikipedia, an information tool, and YouTube, the younger web community’s digital hub, initially suggested the need to further research the way that cyberspace was allowing blatant hate speech to once again flourish within mainstream popular culture. That investigation has led directly to the sources themselves – white power movement websites – where readers of this text might be surprised to find hate speech being voiced through some of the most contemporary internet features such as convergent multi-media centers, social networking forums, and perhaps most troubling of all, research and information tools.

For any website to reach and ultimately engage new members into its cause, both the community and the presentation of its message must identify with the qualities, needs, and desires of a target audience. For the white power movement, that new audience is clearly the white youth of higher education. In fact, that very goal is openly declared by many of the movement’s leaders. Leaders like Matthew Hale, founder of World Church of the Creator, who states, “We generally reach out to the private colleges and universities…because we want to have the elite. We are striving for that, focusing on winning the best and the brightest of the young generation.” This study takes a deeper look into this process of attracting the “best and brightest” of the net generation by considering the white power movement’s most recent adaptation into a model community of cyberspace; fully functional, informative, engaging, and user-friendly.

As a simultaneous exploration of those attributes that are unique to internet youth culture, this book will also consider the ways by which the same traits have become the contemporary tools of the white power movement, enabling them to reconstruct a more modernized message of hate. In the following chapters we will journey to the outer fringes of cyberspace to focus on three central pillars of hate speech on the internet. They are the legal and infrastructural framework, which offers support to the white power movement, the informational component, which creates the illusion of academic legitimacy for the cause, and the cultural context of cyberspace, through which young users are constantly communicating, sharing, learning, and developing new ideas.

Chapter 2 will begin by examining a legal debate that has always surrounded the issue of hate speech in the public domain and is further being tested today on new ground amidst the World Wide Web. In the last decade, new mass communication concerns have arisen from the internet, exclusively, that have indirectly affected the white power movement. Specifically, infrastructural issues such as the internet’s vast unregulated space, its decentralized and unaccountable host networks, and its limitless exposure to younger audiences are all areas that will be considered as the structural building blocks that, for now, benefit the inscribers of online hate speech. This chapter will also look at the ambiguity and challenges inherent in traditional hate speech legislation, such as the landmark case, Chaplinski vs. New Hampshire. Through the vagueness of such existing legislation, we can consider a legal definition of hate speech as something that the white power movement is keenly aware of – and carefully manages to avoid in the new cyber format.

From laws and infrastructure, chapter 3 will next examine the hazy relationship between information and propaganda online. This complex form of persuasive communication has steadily evolved over the years from preexisting strategies of hate speech, war-time rhetoric, and even politics. As a popular research base, the internet is ideal for attracting and “educating” those information-seekers whom the white power groups most wish to recruit – college students. This section primarily addresses key theories of information, propaganda, and the media that have helped hate groups build a path to false knowledge on the internet; what this researcher calls the process of information laundering. This new theory will demonstrate how the formats and constructs of cyberspace can act much like a system of money laundering by taking an illegitimate currency, in this case hate-based information, and transforming it into what is rapidly becoming acceptable web-based knowledge, thus washed virtually “clean” by the system. Through the model of information laundering, hate groups are entering into mainstream culture by attaining legitimacy from the established media constructs of cyberspace, primarily search engines and interlinking networks. These conventional paths can unwittingly lead an online information seeker to white power content that, as later research will show, has already been designed for them as being educational, political, scientific, and even spiritual in nature.

Chapter 4 will address what is perhaps the most important aspect of this subject, the cultural context of cyberspace. Here, we will identify the popular trends that have allowed hate groups to adapt and flourish often under the camouflage of a “user-friendly” social networking community. The data will illustrate how the internet feeds a new culture of youth-built and youth-based activity which happens to meet both the needs and agenda of the white power movement. In this chapter, we will locate and define the qualities of that audience better known as the Net Generation and further identify important constructs of popular online culture. In fact, it is no coincidence that some of the same questions asked here mirror those that are constantly considered by the white power movement. Questions such as which forms of new media do teenagers and college students most visit online? What kinds of websites attract the most users? Why? What social issues speak to the browsing interests of today’s young academic visitor? In a word, it’s about identity. And understanding the personality of a typical internet-user from the net generation can reveal more insight about those hate groups that are attempting to reach them.

Once the foundational, theoretical, and cultural elements of the white power movement in cyberspace have been examined, the next three chapters will present the fruits of their labor. Beginning with chapter 5, we will take a closer look at the 26 websites under review. For this, the white power movement itself will be presented in more exact terms relatable to these web communities of online hate. Like cyberspace itself, the network of the white power arena is vast. From the mainstays of white supremacist society, like the neo-Nazis and skinheads, to next generation racists, such as the Women for Aryan Unity, these homepages truly demonstrate the internet’s boundless potential to be a venue for all kinds of specialized interests.

An initial investigation of these homepages will look at the structural components of URLs like stormfront.org, jewwatch.com, and whitecivilrights.org. From there, research chapters 6 and 7 will delve deeper into the content of these sites by analyzing the packaging of educational and socially-geared messages within them. Through content and frame analysis, the research will peel back the presentation of white power “facts” and “information” and further dissect the underlying language of “friendly forums” in this social network to address two overlying questions. First, how has the white power movement adapted its cause into the information-providing/social networking culture of cyberspace? Second, how do these representative websites frame the white power message for the young-adult-user? These questions will guide a systematic breakdown of these 26 sites with closer attention paid to their mission statements, discussion boards, merchandise, and other measurable multi-media content.

Lastly, chapter 8 will come full circle to the other side of the democratic sphere where some community organizations have built their own websites for the purposes of monitoring hate group activity and promoting a new communication of tolerance. This chapter will highlight the ways that counteractive groups like the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), Southern Poverty Law Center, Simon Wiesenthal Center, and of course, local and federal law agencies are working to combat the white power movement’s progression into the mainstream cyber culture. The private watchdog organizations, in particular, speak to the power of citizen groups on the web that use the same space to employ anti-hate speech measures and teaching tools as their weapons against racism. As Steele asserted in 1996, “The best remedy for hate speech is more speech. And the World Wide Web, which can be expanded infinitely, offers anyone who wishes to set up opposing viewpoints the opportunity to do so.” The civic potential of the web allows these groups to expose hate websites in order to confront the greater issue behind them – intolerance.

Finally, the larger audience will be addressed – that is, the audience of this text, students. As a generation practically born into the internet, this group is perhaps at the greatest risk of falling into the trap of hate websites that are masked as pseudo-communities and research guides. In most cases, for instance, the college audience is twice and even three times removed from the generation that lived through the nightmare of the Holocaust. Does this make them more susceptible to websites that provide so-called proof that this event never actually occurred? Perhaps. The same target audience is also the generation that is rapidly moving away from traditional information sources like books whose paragraphs, pages and chapters are found in the greater context of libraries. Instead they are searching for answers to questions in online search engines, and finding them on homepages. Does this make them less likely to recognize certain fragmented information that is, in fact, well crafted propaganda? In fact, it may, or it may not.

It could be that this audience will be more likely to recognize the falsities and pitfalls of the virtual world and even more aware of hate speech, because of the diversity of this net generation. While, of course, the coming chapters do not attempt to predict the future of an entire generation – only time will tell where the internet age will lead them – one thing is certain. It is this net generation, and not the next, who will have to confront the growing current of hate speech on the internet that is now spilling over into their popular culture. This young audience must learn to recognize all sides of the new democratic sphere in order to safely navigate through the channels of cyberspace. In this incredibly complex age, that recognition process must begin by first understanding what is and what is not racism.

Hate Speech, Radicals, and Codewords

So what is hate speech? As defined by McMasters (1999), hate speech is “that which offends, threatens, or insults groups based on race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or a number of other traits.” When thought of as a functional component to the white power movement’s agenda, hate speech itself should be understood as something more than the mere ranting and raving of a few fanatics. It is, in fact, the technical craft of their trade which has steadily evolved into a multifaceted stream of communication in white power society. Collectively, hate speech should be understood as the strategic employment of words, ideas, images, symbols, news items, social issues, and even pop culture that have all become the complex machinery of effective hate rhetoric – the kind that can recruit a following. The internet, with its own complex machinery of mass communication, has provided the white power movement with a whole new arsenal of possibilities that like any new threat must be investigated and properly understood.

But pursuing a contextual analysis of hate speech can quickly lead the researcher into an unexpected maze of terminology, heated politics and social debate. With every turn, there seems to be a new trap door to avoid or fall through. When does the debate over affirmative action or immigration policy cross a line into racist sentiment? What is the difference between Jewish and Zionist? Does it matter with regard to anti-Semitism? If I am on the far right or the far left of an issue, does that make me a “radical”? How far is too far…?

For American culture, the world’s most diverse society, these questions are a part of life. This can be especially true when issues of race, religion, or sexual orientation enter into the public domain of the news media or popular culture where designations of political correctness are often validated, modified, or challenged. The internet, however, is a much less filtered outlet. The infinite public square of discussion in cyberspace has stripped the boundaries of political correctness and free speech restraints, and in some ways, this can be a good thing. The anonymous nature of the web can provide a more candid and realistic view of American sentiment about race than we would typically receive in our other mass and personal communications. This is a necessary platform to have if we are to move forward as a multicultural society, but the gap between the virtual world and the actual one is wide when it comes to discussing matters of race, and many of those same questions and confusions remain.

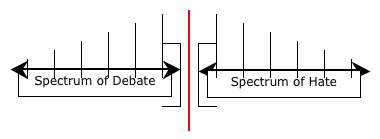

In this research, it is important to provide a guide to approaching hate speech as an identifiable element in society and mass communication. The line that one crosses over from a politically heated debate into racist sentiment may be ambiguous, but it is not absent. This study contends that a strong divide does exist between hate speech and race debate. Whereas some would argue that racism exists at one end of the spectrum and healthy debate at the other, these two forms of communication are separated entirely by motive and emphasis. Those who engage in the debate over affirmative action, for instance, are most likely motivated by political, social, or economic issues, and as such, their contexts place emphasis on matters of jobs, equality, or fairness. Those who engage in hate speech through the affirmative action debate are only really motivated by the issue of identity, and this is seen in their words that place an emphasis on a people rather than the matter at hand. The most common example of this is the superiority/inferiority discourse that is present in most of these faux-political contexts.

When we separate debate and hate speech by their respective motives, public interest and racial identity, it becomes clear that there is not a solid spectrum of communication in all matters of race, but rather two separate lines with debate on one side, and hate on the other. In the United States, however, both forms of expression are protected under the same legal umbrella of the constitution. As we will examine in the next chapter, the First Amendment does not discriminate between a spectrum of debate and the spectrum of hate on the internet. However, in this contextual analysis, there is a functional value in noting not only the separation between the two forms of race communications, but more importantly, the way that white power movement websites borrow from the arguments and appearance of those closest in proximity to them on the farthest end of the debate side. In fact, that is their precise strategy.

In this way, we see a complex dilemma in defining modern hate speech that looks and sounds just like the views of the far right or far left, depending on the issue. Using immigration as an example, at its core this debate is really about the American economy and national security with several perspectives emerging on either side of those arguments. Occasionally, the far right has infused the additional theme of nationalism into the case against immigration, which is not a form of hate speech, but which can be employed to bolster those that are such as hate groups that claim that Hispanic culture threatens white American society. The fact that concepts of nationalism and culture war exist on opposite plains of our working definitions of debate and hate speech is not as significant as the reality that they are only separated by a very thin line. The same narrow divide exists within movements on the far left as well as such racial nationalist groups that express sweeping generalizations about white people or a white government, or the anti-religious movement that tends to vilify all of Judeo-Christian America. Each of these social-political expressions can easily fuel the larger fire of cultural intolerance building in American society regardless of whether or not that is their full intent.

In this 2009 study, some of the current contexts in which we will see white power movement websites exploiting that gray area between politics and radicalism include the issue of racial profiling in America, the president’s nationality, gay marriage, the economic crisis, Wall Street scandals, political elections, and even family table issues like education and health care. Each of these recurring news cycles lends an element of race (some more than others) which the white power movement has keenly learned to utilize as ammunition on their websites. It becomes clear that the new voice of hate speech is now being spoken in the language of our politics, and not the actual racist belief system that lies beneath. So how do we recognize this belief system when we see it? This question brings us to our next contextual trap door, the code language of hate speech.

White power circles in the United States typically target the same minorities, most predominantly, Jews, African-Americans, Latin-Americans, Asian-Americans, and the gay and lesbian community. On occasion, their field of attack widens to include Native Americans, Indian Americans, Muslims, and certain Christian denominations. But, by and large, the typical white power websites and organizations concentrate their agendas on those which they often refer to on their websites as the “mud races.” However, because certain forms of hate speech in America are considered illegal, major hate groups like the National Alliance have learned to carefully direct their cause through more legitimate modes of communication. Enter the new lexicon of bigotry.

Code language in the white power arena is often very benign in appearance. Using some of the same terminologies common to political contexts, more messages of intolerance are being veiled beneath the cloak of socially accepted vernaculars. For example, the common expression “anti-American” seemingly denotes someone whose views are in opposition to the values of the United States and its people. In the online world of hate groups, however, anti-American refers to anyone that actively supports multicultural and progressive movements or that does not belong to the fabric of white society. The term is more frequently found within the context of radical right websites, meant to strike a cord with patriots that would naturally identify with any group of people claiming to be a part of “real” America. Of course, such language of exclusion is by design and intended to reach everyday white citizens who obviously would identify themselves as pro-American.

Like anti-Americanism, Zionism is another codeword often found in anti-Semitic corners of cyberspace. Zionism is commonly defined as the “movement for national revival and independence of the Jewish people in “Eretz Yisrael” (Israel by its biblical name). Within the walls of white power websites, however, Zionism and Zionists mean but one thing – Jews. This intended conflation of meanings is a prime example of the white power movement hiding behind politically-acceptable language that does not directly implicate a people, but rather a movement identified with their ethnicity. In some circles, it considered “fair play” to denigrate the Zionists as a people because there is a political context that exists between that word and the people it truly indicates. Many could therefore presume that the white power movement is staying safely within the boundaries of the spectrum of debate when they attack Zionists but not Jews, immigrants but not Hispanics, non-Europeans but not African-Americans, and anti-Americanism but not American multiculturalism – all code words for hate. As chapter three will later demonstrate, it is often, in fact, the more benign-sounding language of encoded hate speech that has proven to be the most deadly.

Conclusion

Throughout history, powerful effects of propaganda – what many media scholars commonly deem the “hypodermic needle” of mass communication – have been crafted through encoded racist sentiments and erroneous political causes in the media. The popular Nazi newspapers and radio broadcasts of the 1930s spoke directly to this point by consistently writing of a great Aryan heritage comprised of blonde hair and blue-eyed Germans, while at the same time, reporting on Jewish fraud in the business and academic fields. Encoded, these sentiments played out perfectly with a struggling German society to convey the idea that Jews were not part of this great future Aryan Fatherland, but rather were the people behind a deep conspiracy to control it. By the late 1930s most German citizens did nothing when their Jewish neighbors were being taken from their houses and thrown into cattle cars to destinations unknown, but suspected.

As the grandson of two Holocaust survivors of the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps, my study of hate speech has emanated from a desire to pursue the unanswered question of how the fever of racist sentiment can so thoroughly sweep over a civilized society as it did in 1930s Germany and other parts of Europe. Any research of the Holocaust will reveal that the systematic removal of Jews from society did not begin with the national march of anti-Semitic rallies through Nuremberg or the riots of Cristalnacht, the Night of Broken Glass. It began in the popular editorials of German newspapers like Der Sturmer and the political cartoons that depicted mainstream vilifications of the Jews. It began in the fringe media. These were the Nazi’s greatest allies for turning the whole of German society against an entire people who had lived peacefully within their borders for centuries.

Understanding what constitutes hate speech today requires recognizing the same elements that were fundamental to the Nazi’s formula: the courier, the message, and the medium. As we have already seen, the couriers of modern racism are a highly organized community of hate groups and individuals who are as multigenerational as they are media-savvy. While some may identify themselves as supremacists and others as separatists, their ideal American society is one and the same, white. The messages they deliver range across a wide spectrum of legally-protected hate speech, from outright and transparent bigotry to the evermore desirable gray area of race politics. To attain the type of mainstream following the Nazis achieved, today’s couriers of hate are using a new medium that can reach millions in a matter of seconds, but most importantly, their number one target audience. That medium is the internet, and its most common subscribers are the young adults of the net generation. We will soon see how the functions and formats of cyberspace accommodate both the needs of everyday young Americans, and at the same time, the agenda of white supremacist subculture. In this new dynamic, the latter will attempt to use the filters of education in cyberspace and social networks to interconnect their message of a white power uprising into the mainstream culture of the new media.

– Adam Klein